Announcement

NAACP Led in Creating the 1963 March on Washington

The 1963 March on Washington (MOW) was the implementation of A. Philip Randolph’s original threat in 1941 to stage a march on the national capital of 100,000 blacks if President Franklin Roosevelt did not take definite steps to end racial discrimination in the World War II defense industry. To stave off the march, Roosevelt responded by issuing Executive Order 8802 on June 25, 1941, barring discrimination in the defense industry based on race, color, creed and national origin and creating the Fair Employment Practice Committee as a wartime implementing agency. This action resulted in the launching of the modern civil rights movement. From then, African Americans made their demand for presidential leadership to end discrimination and segregation a defining principle in their struggle for racial equality. [Volumes 1 and 2 Papers of Clarence Mitchhell, Jr., edited by Denton L. Watson]

In 1963, as Congress adamantly refused to pass a much-needed civil rights bill, Randolph once urged that the civil rights organizations lead a massive march on Washington to achieve that goal. Joseph L. Rauh, as a young lawyer who in 1941 had written Executive Order 8802, and was co-founder of Americans for Democratic Action and legal counsel for the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, the 1960s lobbying group created by the NAACP, recalled how the 1963 MOW developed, accordingly:

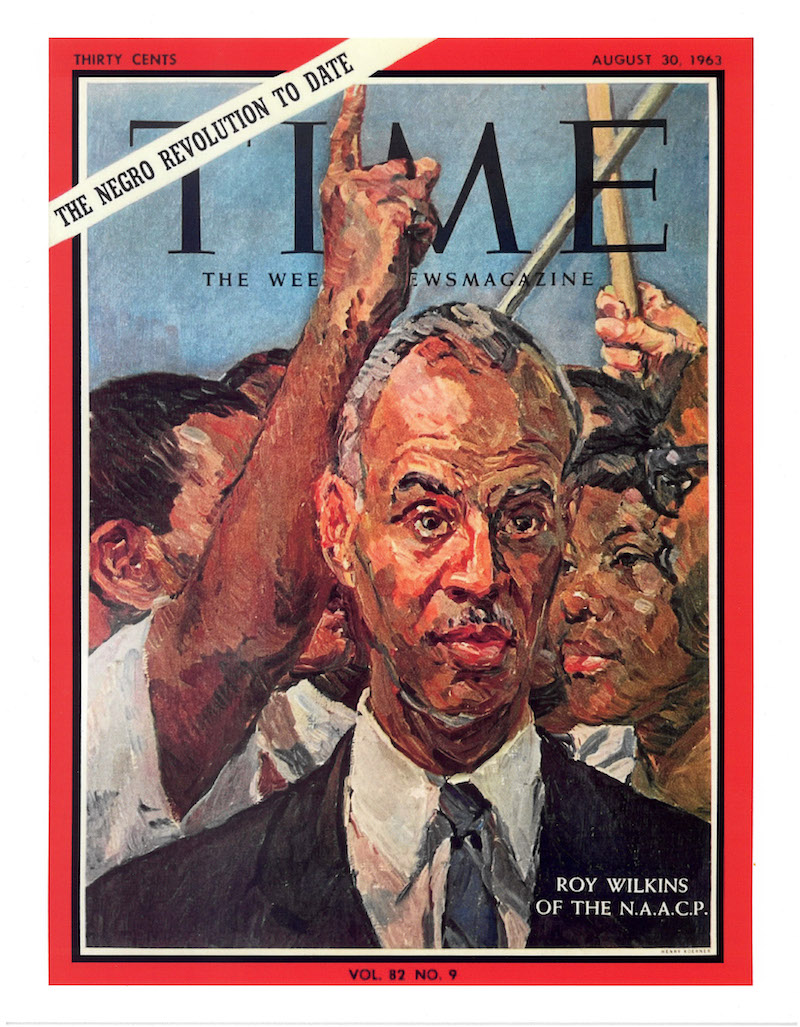

Roy Wilkins, who was chairman of the Leadership Conference as well as NAACP executive secretary, promptly called a meeting for July 2, 1963 at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York. Not only were the 50 long-time civil rights organizations then in the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, but another 50 or so religious and other potentially helpful groups were also asked to come. The mood was one of excitement that, at long last, there was a bill in the hopper worthy of a real struggle. The consensus was easily arrived at. The civil rights movement gave its wholehearted support to the Kennedy administration bill. But it – that is, the NAACP, and the Leadership Conference -- demanded more – an FEPC, Part III [authority for the attorney general to protect Fourteenth Amendment rights and] all public accommodations covered. Not only were these additional provisions urgently needed, but the NAACP felt that a good offense was obviously the best defense against weakening amendments [in JFK’s pending civil rights bill]. [Rauh, “The Role of the Leadership Conference,” in Robert Loevy, The Civil Rights Act of 1964, p. 54.]

Wilkins himself reported on the initial steps leading to the MOW, accordingly:

The first meeting [at the New York Roosevelt Hotel] was attended by representatives of CORE (James Farmer); Southern Christian Leadership Conference (Martin Luther King); Urban League (Whitney Young); Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (John Lewis); Negro American Labor Council (Philip Randolph) NAACP (Wilkins). The March on Washington was conceived by Mr. Randolph last spring as a protest on unemployment to be held in the fall, but the developments on the civil rights front caused the date to be advanced to August 28. The tentative budget is $65,000. Each organization pledged financial support. The plan is for an orderly march of over 100,000 people. Wilkins next reported accordingly:

[NAACP National Board of Directors Minutes, July 3, 1963.]

MARCH ON WASHINGTON: September 9, 1963)

More than 210,000 persons assembled in Washington, D. C., on August 28, at the Lincoln Memorial, following a march from the Washington Monument where it originated. Thirty percent of the crowd was white.

The major part of the Secretary’s time, as well as other staff members’, during July and August was taken up with plans for making the event a successful one.

The March for Jobs and Freedom, a peaceful protest participated in by persons, white and Negro, from all parts of the country, was the greatest event of its kind in the history of the country. There were 21 special trains, some from the South and Midwest, others from the Eastern Seaboard. The official count on chartered buses was 1,514. The spirit of the people and their order completely confounded those who had prophesied disorder and violence.

The program was over at 4:15 PM and the first special train returning home left at 5:10PM. The last bus left the city at 9:20PM. Preparation had been made to care for 5,000 stragglers overnight, but only 128 required care.

Representatives of the sponsoring organizations addressed the group: A. Philip Randolph, Chairman of the March, representing the Negro American Labor Council, presided; the Executive Secretary; Dr. Martin Luther King of SCLC: Floyd McKissick representing James Farmer of CORE who was in jail in Donaldsonville, La.; Whitney M. Young, Jr., of the National Urban League; John Lewis of SNCC; Walter Reuther of the UAW CIO representing labor; representatives of the three major faiths --Dr. Eugene Carson Blake of the National Council of Churches; Mathew Ahmann of the National Catholic Conference on Interracial Justice; and Rabbi Joachim Prinz of the American Jewish Congress.

There were no incidents to mar the day. Only four persons were arrested, none of whom was involved in the March.

Marian Anderson, Camilla Williams, the Eva Jessye Choir and Mahalia Jackson were on the regular program.

A corps of newspaper correspondents, radio and television reporters and commentators, as well as representatives from many countries of the world covered the March. A variety of celebrities of screen and stage participated. Goals: The March listed as its goal ten separate demands to gain full civil rights: Comprehensive and effective --civil rights legislation from the present Congress—without compromise or filibuster—to guarantee all American access to all public accommodations, decent housing, adequate and integrated education and the right to vote. It requested the withholding of Federal funds from all programs in which discrimination exists, desegregation of all school districts in 1963, enforcement of the Fourteenth Amendment—reducing the Congressional representation of states where citizens are disfranchised. It cited the need for an executive order banning discrimination in all housing supported by Federal funds, authority for the Attorney General to institute injunctive suits when any constitutional right is violated, a massive Federal program to train and place all unemployed workers – Negro and white – on meaningful and dignified jobs at decent wages. Also a national minimum wage act that will give all Americans a decent standard of living (government surveys showed that anything less than $2.00 an hour fails to do this), a broadened Fair Labor Standards Act to include all areas of employment which are presently excluded and a Fair Employment Practices Act barring discrimination of federal, state, and municipal governments, and by employers, contractors, employment agencies, and trade unions. Meeting With Congressional Leaders : During the morning of the 28th, prior to commencement of the March, the ten co-chairmen of the March held a series of conferences with Congressional leaders including Speaker John McCormack, Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield, Minority Leader Everett McKinley Dirksen and Representatives Carl Albert and Charles Halleck.

Meeting With President: Immediately following the March, the ten co-chairmen met at the White House with President Kennedy for 75 minutes. At the close of the meeting, the President issued the following statement:

We have witnessed today in Washington tens of thousands of Americans—both Negro and white---exercising their right to assemble peaceably and direct the widest possible attention to a great national issue. Efforts to secure equal treatment and equal opportunity for all without regard to race, color, creed, or nationality are neither novel nor difficult to understand. What is different today is the intensified and widespread public awareness to move forward in achieving these objectives—objectives which are older than this nation.

Although this summer has seen remarkable progress in translating civil rights from principles into practice, we have a very long way yet to travel. One cannot help but be impressed with the deep fervor and the quiet dignity that characterizes the thousands who have gathered in the nation’s capital from across the country to demonstrate their faith and confidence in our democratic form of Government. History has seen many demonstrations – of widely varying character and for a whole host of reasons. As our thoughts travel to other demonstrations that have occurred in different parts of the world, this nation can properly be proud of the demonstration that has occurred here today. The leaders of the organization sponsoring the march and all who have participated in it deserve our appreciation for the detailed preparations that made it possible and for the orderly manner in which it has been conducted.

The executive branch of the Federal Government will continue its efforts to obtain increased employment and to eliminate discrimination in employment practices, two of the prime goals of the March. In addition, our efforts to secure enactment of the legislative proposals made to the Congress will be maintained, including not only the civil rights bill but also proposal to broaden and strengthen the manpower development and training program, the youth employment bill, amendments to the vocational education program, the establishment of a work-study program for high school age youth, strengthening of the adult basic education provisions in the Administration’s education program and the amendments proposed to the public welfare work-relief and training program. This nation can afford to achieve the goals of a full employment policy—it cannot afford to permit the potential skills and educational capacity of its citizens to be unrealized. The cause of 20,000,000 Negroes has been advanced by the program conducted so appropriately before the nation’s shrine to the Great Emancipator, but even more significant is the contribution to all mankind.

Watson, in Lion in the Lobby, writes:

The climate of militancy in 1963 was further heightened by the revival of Philip Randolph’s twenty-two-year-old dream for a march of one hundred thousand African Americans on Washington for “jobs and freedom.” The march idea was revived a few days before January 1 – exactly a century after the Emancipation Proclamation – by Bayard Rustin; his friend Tom Kahn, a lanky white student at Howard University; and Norman Hill, a slightly built program director for CORE. They prepared a memo for Randolph that urged it was time to dramatize the need for jobs for blacks with a mass march on Washington. A problem afterward with Randolph’s first announcement was that he had consulted no other civil rights leader before going public. He simply told a reporter offhandedly that “we’re going to march.” Now Randolph invited several other organizations to participate – but not the SCLC, apparently because King had tried to co-opt the march idea. Wilkins confirmed this when, in dismissing the call by King to march, he said, “somebody just made a premature announcement. I had discussed the plans with A. Philip Randolph six months ago. It was his idea.” On June 22, a few weeks after Randolph’s second call following a White House meeting between Kennedy and a group of civil rights and labor leaders, Walter Reuther suggested to Randolph that he broaden the march to include all the major protest groups, and he agreed. On July 2, about thirty civil rights, religious and labor leaders held their first follow-up meeting – a “summit conference,” as the press billed it – at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York to begin implementing a March on Washington (MOW) program that the NAACP had presented. While those plans were developing, Mitchell concentrated on implementing an NAACP convention resolution he had gotten adopted for a national “Legislative Strategy Conference on Civil Rights.”

The NAACP Legislative Conference, held on August 6-7 at the Washington Statler-Hilton Hotel, was distinct in scope and purpose from Randolph’s proposed August 28 MOW. It provided local NAACP leaders with a thorough briefing on pending civil rights legislation, enabled them to meet with their representatives in the House and Senate from whom they sought commitments of support, and developed plans for consistent and continued grassroots activity back home. The NAACP Washington Bureau summarized for its troops the obstacles to passing legislation in Congress and the NAACP basic strategy for maneuvering though the parliamentary minefield in the House and Senate. . . . Watson, Lion in the Lobby, pp. 570-571

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Mitchell assumed a commanding role in planning the March on Washington, which was intended to reinforce the legislative conference by bringing public pressure, in addition private, to bear on Congress and the White House. First, with the help of Wilkins, whose blessings were necessary for success, he moved to ensure that the stated purpose of the march, “jobs and freedom,” was supported with the specific demand for passage of civil rights legislation in Congress. The MOW, among other things, listed ten civil rights demands. The first was comprehensive and effective legislation to guarantee all Americans access to public accommodations, decent housing, adequate and integrated education, and the right to vote. It requested the withholding of federal funds from all programs that discriminated, desegregation of all school districts in 1963, enforcement of the Fourteenth Amendment and a reduction of congressional representation in states where citizens were disfranchised.

The purpose of the MOW was also to focus national attention on the need for an executive order banning discrimination in all housing supported by federal funds, authority of the attorney general to institute injunctive suits when any constitutional right was violated, and a massive federal program to train and place all unemployed workers on meaningful and dignified jobs at decent wages. The MOW called for a national minimum wage act that would give all Americans a decent standard of living, a broadened Fair Labor Standards Act to include all areas of employment that were excluded, and a fair employment practices act barring discrimination by federal, state, and municipal governments, and by employers, contractors, employment agencies, and trade unions.

Bayard Rustin, as the MOW’s field marshal, was responsible for keeping the several rival organizations involved working together and for issuing rapid-fire volleys of bulletins, press releases, handbooks, charts, schedules, and all other necessary minutiae of planning. Four other officially designated leaders representing the AFL-CIO and Protestants, Catholic and Jewish organizations, the white participants, were included. The march would go only eight-tenths of a mile from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial, but the logistics were a nightmare. Rustin enlisted Mitchell’s help on the MOW because he needed someone with clout to pull together people from the various agencies, particularly since the President opposed the march.

With Wilkins’ approval, Rustin got Mitchell to direct the planning of such details as obtaining 3,000 to 4,000 Army blankets for early arrivals on the Washington mall, persuading U.S. Health, Education and Welfare Department to develop menus; coordinating the work of the FBI and the local police; arranging with the city for local stores to be closed the day of the march; and providing toilets, portable water fountains a raincoat first aid stations, manned by forty doctors, and eighty nurses, and ambulances to be scattered under the Washington Monument and along the march route. Planners urged marchers to bring plenty of water but no “alcoholic refreshments.” Peanut butter and jelly sandwiches were appropriate but nothing with mayonnaise “as it deteriorates, and may cause serious diarrhea.” They reminded everyone to wear low-heeled shoes, to bring a hat and sunglasses. Children were to be left at home. Much of the logistical planning was done by a committee headed by Clarence Mitchell and Rustin that held weekly meetings at which representatives of the various federal and city agencies were present. People don’t know, but Clarence Played a major role,” said Rustin. Watson, Lion in the Lobby, pp. 573 -574.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

New Volumes

The Struggle to Pass the 1957 Civil Rights Act

Volume Five, 1955–1957

The 1957 Civil Rights Act was the first successful lobbying campaign by an organization dedicated to that purpose since Reconstruction. Building on the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, the law marked a turning point for the legislative branch in the struggle to accord Black citizens full equality under the Constitution.

The Struggle to Pass the 1960 Civil Rights Act

Volume Six, 1959–1960

The Civil Rights Act of 1960 attempted to rectify loopholes in the 1957 Civil Rights Act that had enabled southern states to continue disenfranchising Black voters and, in Texas, Mexican Americans. The legislation called for federal inspection of voter registration polls and introduced penalties for obstructing a person from registering to vote.

The Civil Rights Act of 1960 attempted to rectify loopholes in the 1957 Civil Rights Act that had enabled southern states to continue disenfranchising Black voters and, in Texas, Mexican Americans. The legislation called for federal inspection of voter registration polls and introduced penalties for obstructing a person from registering to vote.

“Clarence Mitchell Jr. for decades waged in the halls of Congress a stubborn, resourceful and historic campaign for social justice. The integrity of this ‘101st Senator’ earned him the respect of friends and adversaries alike. His brilliant advocacy helped translate into law the protests and aspirations of millions consigned for too long to second-class citizenship. The hard-won fruits of his labors have made America a better and stronger nation.”

— President Jimmy Carter

Project Overview

So legendary was Clarence Mitchell, Jr., as a civil rights lobbyist in Congress that he was popularly called the “101st senator.” He led the NAACP’s struggle for passage of the civil rights laws and adoption of constructive national policies for the protection of the civil rights of African Americans by the executive branch. This struggle was rooted in the egalitarian philosophy of the Declaration of Independence and shaped by reason and carefully documented factual evidence. The core documents pertaining to the legislative struggle, approximately 45,000 occupying 83.2 linear feet of shelf space, are in the NAACP Washington Bureau collection at the Library of Congress. They, as well as Mitchell’s personal papers held by his family and others that were collected by this author were used in the biography, Lion in the Lobby, Clarence Mitchell, Jr.’s Struggle for the Passage of Civil Rights Laws. It was first published by William Morrow and Company in 1990 and reissued by University Press of America in 2003. No comparable collection documenting the struggle for the civil rights laws exists in any other place. The papers document how the NAACP worked within the government to obtain passage of the civil rights laws. They provide the most detailed record of Mitchell’s success in getting the Legislative Branch to join the Judicial and Executive branches to provide protections for civil rights. The Papers of Clarence Mitchell, Jr., project is publishing the weekly, monthly and annual reports prepared by Mitchell from 1942 to 1978. The other five categories in his collection are his memoranda, letters and telegrams, congressional testimonies, speeches, and newspaper columns and scholarly articles.

The Papers of Clarence Mitchell Jr. documents the contributions of eight presidents to the establishment and enforcement of a national civil rights program. They provide the foundation for assessing the contributions to the civil rights struggle of the armed services, the justice department and other federal agencies during their administrations. The papers document how “Desegregation by Presidential Order” was achieved (June 29, 1954 report). They show how Mitchell developed the evolutionary strategy in Congress for winning passage of the 1957 Civil Rights Act, the first such measure in 82 years, the 1960 Civil Rights Act, the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the 1965 Voting Rights Act, the 1968 Fair Housing Act, and the adoption of constructive national policies for enforcing those laws.

The documentary editing project is sponsored by SUNY College at Old Westbury and funded by the NHPRC